Police to attend burglaries within an hour, under new rules

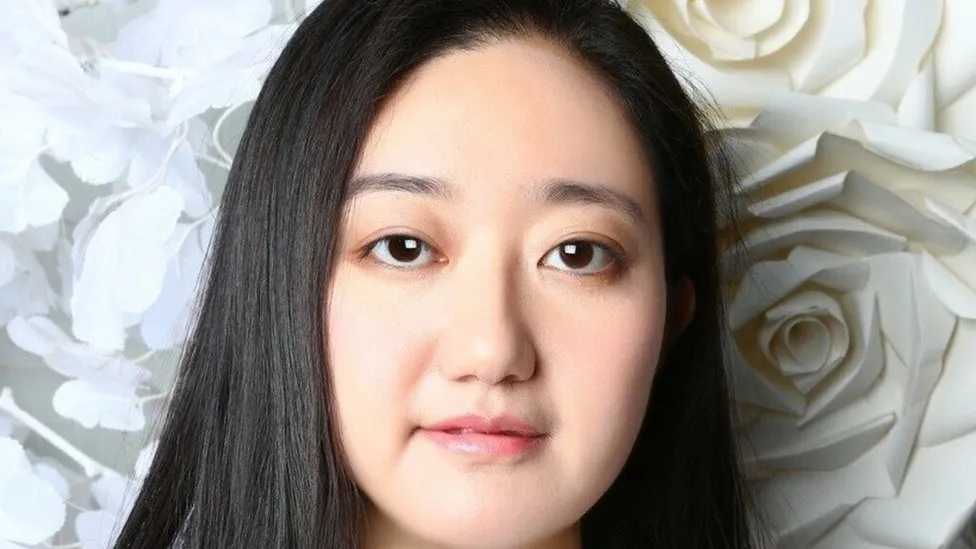

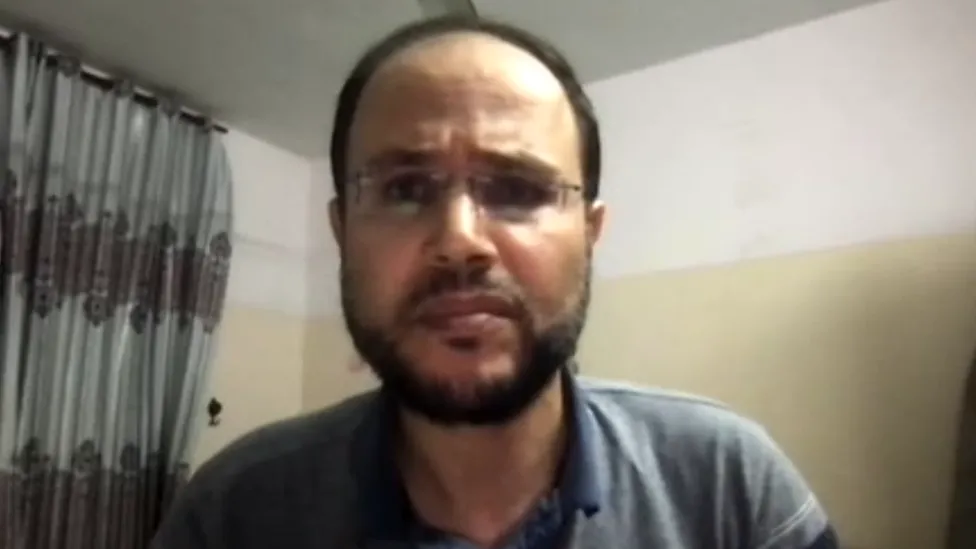

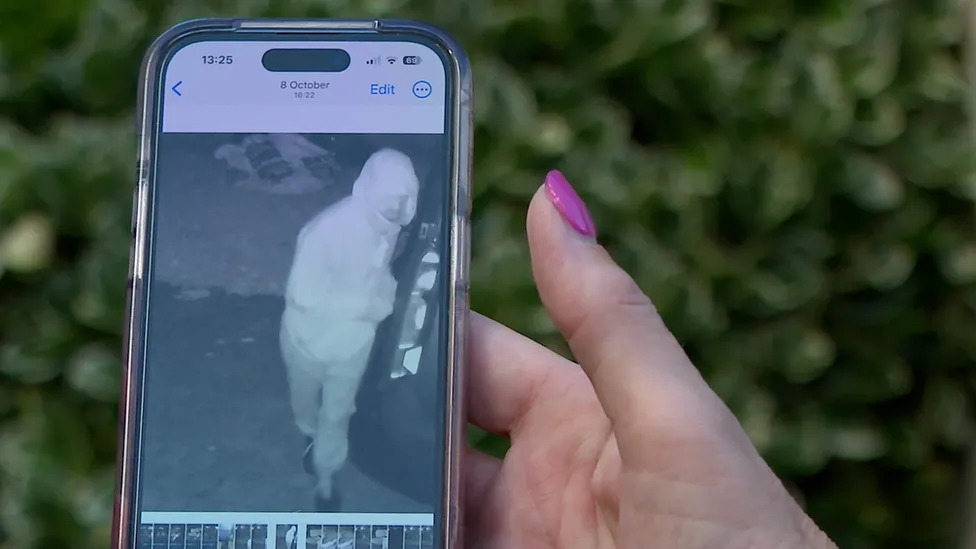

After a burglar stole thousands of pounds worth of power tools from her home, in St Albans, in October, Sharon Allen turned amateur detective.

She began going house to house, making her own inquiries, and handed CCTV footage from her neighbours to police.

“He’s got a distinctive nose,” Ms Allen tells BBC News, as she examines her own black-and-white security-camera footage.

“I’ve given them the information and I’m hoping they’ve looked at the CCTV.”

An officer visited her home – but Ms Allen has heard nothing since.

The burglar is still in the area, she says, and has been seen hanging around nearby shops.

“I realise I’m not the first on the list – but I’d like to think that they will look into it,” Ms Allen says.

But Hertfordshire Constabulary has one of the worst burglary clear-up rates in the country.

In St Albans – a cathedral city of 148,000 people, just 25 miles (40km) north of central London – although some officers are based at its civic centre, there has been no police station open to the public since 2015.

“I do understand they’re very busy and there’s other things going on,” Ms Allen says.

“Maybe it needs to go back to more bobbies on the beat, panda cars driving around and just keeping an eye on things – because this person, he’s still around.”

Police chiefs have been under pressure to improve their response to domestic break-ins.

No suspect is identified in three-quarters of all residential break-ins in England and Wales, according to the latest Home Office figures, with someone charged in less than 4% of cases.

Shortly after her appointment, in 2022, former home secretary Suella Braverman wrote to all forces telling them the public wanted to know an officer would visit them after a burglary.

And now, new national policing guidance says officers should prioritise attending the scene of a domestic break-in within an hour of the report, increasing the chances of solving the case.

“Golden hour” enquiries “may make the difference between early identification and arresting a suspect and/or recovering stolen property or not”, it says.

Investigations should include:

- forensic tests

- searches

- interviewing neighbours

- obtaining CCTV from doorbells or security cameras

“The average number of burglaries that are detected is around about 5%,” NPCC burglary lead Deputy Chief Constable Alex Franklin-Smith says.

“We don’t believe that’s good enough. We don’t think the public would think that’s good enough. So that is very much where our focus is at the moment.”

A two-year trial of this new approach to burglary has seen Greater Manchester Police raise the proportion resulting in charges from 3% to almost 8%.

“The previous focus, I think, did take the eye off the ball in terms of burglary,” Supt Chris Foster, who leads the force’s Operation Castle, says.

“Previously, it’s been, ‘We can’t do anything about it, sorry. See you later, goodbye – crime closed.’

“Now, we arrest more people – and burglary rates are falling.”

“If we turn up properly, investigate properly, arrest people and make sure that we explain our actions, even if it is negative, that begets confidence in the police.”

Rolling pin

Burglaries are often difficult to solve and there has been debate about throwing resources at cases where little of value has been stolen and the chances of finding the perpetrator are so low.

But many victims complain police will not look at CCTV images of the burglar and sometimes not even attend the crime scene.

Despite public concern, burglary has fallen by about 80% since the mid-1990s, in England and Wales.

But there are still more than 1,000 break-ins every day and the psychological impact can be devastating.

Supt Foster’s determination to catch burglars stems from when he was just eight years old.

“I came home and we’d been burgled,” he says, “and there was a footprint on the windowsill

“I couldn’t sleep that night – I had to go to bed with a rolling pin under the bed.

“And I think we forget it’s not just financial loss – someone’s been in your house.”

No suspect

It is this emotional impact of domestic burglary, the violation of someone’s home, that has prompted the police’s rethink.

Even if very little of value has been stolen, victims need to believe officers will respect and respond to their trauma.

Ms Allen has now waited almost three months for any progress in her burglary.

A Hertfordshire police spokesman told BBC News: “All lines of enquiry have been exhausted in the case – no suspect has been identified.

“Should any new investigative opportunities become available, they will be acted upon accordingly.”

Additional reporting: Abiona Boja and Callum May